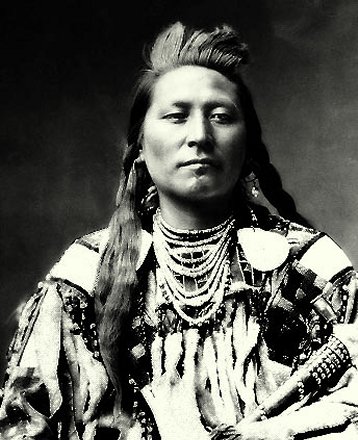

Philosopher and psychoanalyst Jonathan Lear finds the human soul in Aristotle, Freud, and the Crow Nation’s last chief.

Lear first heard these lines at a Yale lecture on historiography. Two decades later, during a walk along the Chicago lakefront, Plenty Coups’s words came back to him. “And I realized that this had happened before,” he says. “It took me 20 years to notice that after 20 years, it hadn’t gone away. I suddenly thought, I need to find out what this means.” Shortly afterward, the World Trade Center towers fell, and in the newspapers and magazines Lear reads—the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Economist, Harper’s, The New Republic, the Times Literary Supplement—he noticed “a rising sense of anxiety about civilization’s vulnerability.” What can it mean, he wondered, for a leader to say about his nation that after a certain point, nothing happened? And what connection might that assertion have to current cultural fears, which Lear believes fuel anger across the globe?

His meditation resulted in Radical Hope (Harvard University Press, 2006), a book that examines whether it is possible to maintain hope in a meaningful existence even as one’s own existence loses all meaning. “That is radical hope,” Lear says. “It is radical because it’s a hopefulness that outstrips the ability to formulate proper concepts with which to hope.” Culturally unmoored, one hopes without knowing what for. “Even though your inherited understanding of what you could do and who you could be falls apart, you trust sufficiently in the goodness of the world to endure a period in which, for instance, the question of what is courage has no answer.”

Plenty Coups guided the Crow through such an abyss, from a world in which stealing an enemy’s horse was a triumph into a world in which it was theft. As Japan industrialized in the late 1800s, Lear notes, the samurai faced a similar calamity. (He regards the Holocaust as a separate tragedy: Jewish culture didn’t break down but gained meaning from survival in spite of Nazi persecution.) “Or take Don Quixote,” Lear says. “He wants to be a knight errant, but there’s no way to be a knight errant. Part of what makes it such a deep comedy is he’s insisting on being something it’s no longer possible to be.”

Unlike Don Quixote or Plenty Coups’s Sioux rival Sitting Bull, the Crow chief did not insist. Faithful to a dream-vision he’d had as a nine-year-old boy, he steered his followers peacefully onto their Montana reservation in 1892. Their old existence ended, but he sought to forge a new one in the white world.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.