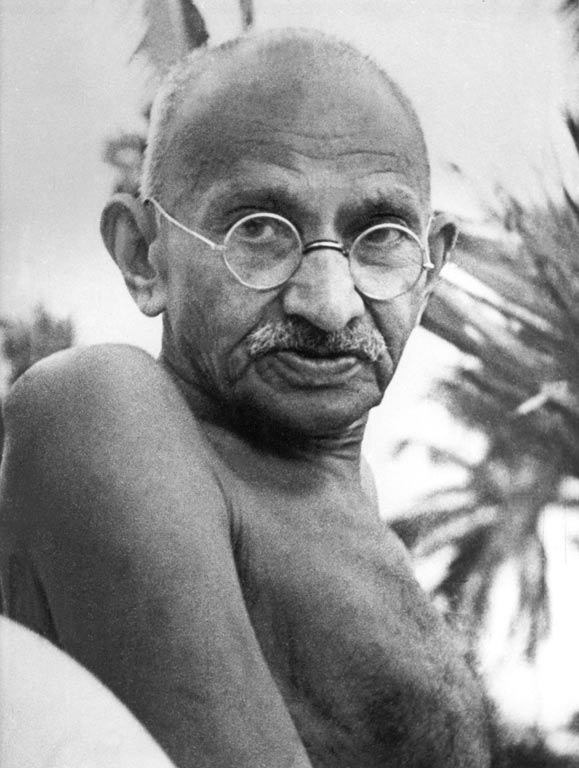

Nonviolence

Although Mahatama Gandhi was not the originator of the principle of non-violence, he was the first to apply it in the political field on a huge scale. The concept of nonviolence (ahimsa) and nonresistance has a long history in Indian religious thought and has had many revivals in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Jewish and Christian contexts. Gandhi explains his philosophy and way of life in his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth. He was quoted as saying:

"When I despair, I remember that all through history the way of truth and love has always won. There have been tyrants and murderers and for a time they seem invincible, but in the end, they always fall—think of it, always."

"What difference does it make to the dead, the orphans, and the homeless, whether the mad destruction is wrought under the name of totalitarianism or the holy name of liberty and democracy?"

"An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind."

"There are many causes that I am prepared to die for but no causes that I am prepared to kill for."

No, Gandhi is relevant here because his values stand in contrast to the dominant Western values the colonialist powers imposed on the world.

Although America called its indigenous population "savages," "killers," and "scalpers," many Indians sought nonviolent means of accommodation. They sued for peace, signed treaties, resisted passively, fled, or stayed in place and did nothing.

It would've been interesting if the Ghost Dance movement of the late 19th century turned into a full-fledged campaign of civil disobedience. It might not have worked, but violent reprisals didn't work either. Geronimo and his guerrilla band ended up in the same prison camp as the Apaches who settled into farming on reservations.

For more on the subject, see Winning Through Nonviolence.

He also admired Hitler and thought the Jews should have gone meekly into the camps.

ReplyDeletehttp://koenraadelst.bharatvani.org/articles/fascism/gandhihitler.html

ReplyDeleteOn this occasion, Gandhi took the trouble of justifying his addressing Hitler as "my friend" and closing his letter with "your sincere friend," in a brief statement of what exactly he stood for: "That I address you as a friend is no formality. I own no foes. My business in life has been for the past 33 years to enlist the friendship of the whole of humanity by befriending mankind, irrespective of race, colour or creed." This very un-Hitlerian reason to befriend Hitler, what Gandhi goes on to call the "doctrine of universal friendship," contrasts with the Hitler-like hatred of one's enemy which is commonly thought to be the only correct attitude to Hitler.

Gandhi certainly earns the ire of post-war public opinion by stating: "We have no doubt about your bravery or devotion to your fatherland, nor do we believe that you are the monster described by your opponents." To be sure, this was written in a period of fairly limited warfare, well before the total war with the Soviet Union and the USA, and well before the mass killing and deportation of Jews. But the prevailing attitude today is one of judging Hitler and his contemporaries' dealings with him as if they all had the knowledge that we have acquired in and since 1945. By that standard, anyone doubting the British government's hostile depiction of Hitler, including Gandhi, was practically an accomplice to Hitler's crimes.

However, while not giving up on the chance of converting Hitler to more peaceful ways, Gandhi was not that mild in judging the crimes Hitler had already committed. In particular, he criticized the already well-publicized Nazi conviction that the strong have a right to subdue the weak: "But your own writings and pronouncements and those of your friends and admirers leave no room for doubt that many of your acts are monstrous and unbecoming of human dignity, especially in the estimation of men like me who believe in human friendliness. Such are your humiliation of Czechoslovakia, the rape of Poland and the swallowing of Denmark. I am aware that your view of life regards such spoliations as virtuous acts. But we have been taught from childhood to regard them as acts degrading humanity."

So, Gandhi felt forced to join the ranks of Hitler's opponents: "Hence we cannot possibly wish success to your arms." Yet this did not make him join the British war effort nor even some non-violent department of the British Empire's cause: "But ours is a unique position. We resist British imperialism no less than Nazism." To Gandhi, British imperialism is closely akin to Nazi imperialism: "If there is a difference, it is in degree. One-fifth of the human race has been brought under the British heel by means that will not bear scrutiny."

In outlining his position vis-à-vis British imperialism, Gandhi at once explained his attitude vis-à-vis Nazism: "Our resistance to it does not mean harm to the British people. We seek to convert them, not to defeat them on the battle-field." This was exactly what Gandhi was now trying out on Hitler: to convert him rather than defeat him, thus sparing him defeat if only he had listened.