How the Native American extermination campaigns merged the dangerous forces of a standing army with the business/political interests of the Republican Party.

By Thomas DiLorenzo

How the situation started:

Trade and cooperation with the Indians were much more common than conflict and violence through the first half of the 19th Century.

Terry Anderson and Fred McChesney relate how Thomas Jefferson found that during his time negotiation was the Europeans’ predominant means of acquiring land from Indians. By the 20th Century, some $800 million had been paid for Indian lands.

Perhaps trade and cooperation were much more common in the 18th century. In the first half of the 19th century, it was more like 50% cooperation and 50% conflict. In the last half of the 19th century, it became almost 100% conflict.

Civil War ended...what's next?

How the situation changed after the Civil War:

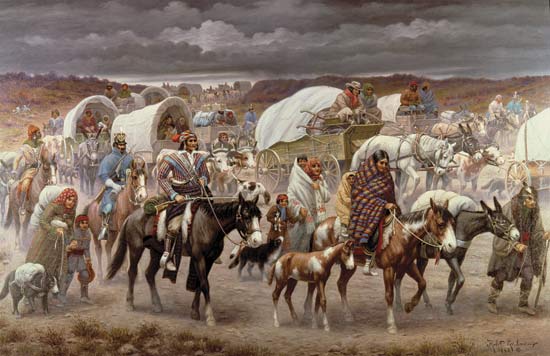

The change from militia to a standing army took place in the American West immediately upon the conclusion of the War Between the States. The result, write Anderson and McChesney, was that white settlers and railroad corporations were able to socialize the costs of stealing Indian lands by using violence supplied by the U.S. Army.

On their own, they were much more likely to negotiate peacefully. Thus, “raid” replaced “trade” in white–Indian relations. Congress even voted in 1871 not to ratify any more Indian treaties, effectively announcing that it no longer sought peaceful relations with the Plains Indians.

Sherman received this command for the purpose of commencing the 25-year war against the Plains Indians, primarily as a form of veiled subsidy to the government-subsidized railroad corporations and other politically connected corporations involved in building the transcontinental railroads.

These corporations were the financial backbone of the Republican Party. Indeed, in June 1861, Abraham Lincoln, former legal counsel of the Illinois Central Railroad, called a special emergency session of Congress not to deal with the two-month-old Civil War, but to commence work on the Pacific Railway Act.

Subsidizing the transcontinental railroads was a primary (if not the primary) objective of the new Republican Party.

“We are not going to let a few thieving, ragged Indians check and stop the progress [of the railroads],” Sherman wrote to Ulysses S. Grant in 1867. [See Michael Fellman’s Citizen Sherman: A Life of William Tecumseh Sherman.]

How to eliminate the Indians

The final solution to the "Indian problem":

“Thus the great triumvirate of the Union Civil War effort,” writes Sherman biographer Michael Fellman, “formulated and enacted military Indian policy until reaching, by the 1880s, what Sherman sometimes referred to as ‘the final solution of the Indian problem.’”

What Sherman called the “final solution of the Indian problem” involved “killing hostile Indians and segregating their pauperized survivors in remote places.”

“These men,” writes Fellman, “applied their shared ruthlessness, born of their Civil War experiences, against a people all three [men] despised. … Sherman’s overall policy was never accommodation and compromise, but vigorous war against the Indians,” whom he regarded as “a less-than-human and savage race.”

All of the other generals who took part in the Indian Wars were “like Sherman [and Sheridan], Civil War luminaries,” writes Sherman biographer John Marszalek. “Their names were familiar from Civil War battles: John Pope, O. O. Howard, Nelson A. Miles, Alfred H. Terry, E. O. C. Ord, C. C. Augur . . . Edward Canby . . . George Armstrong Custer and Benjamin Garrison.” General Winfield Scott Hancock also belongs on this list.

Our national mythology of cowboys and Indians came about precisely because we were prosecuting a war against the Indians. Thus we cast ourselves as the brave, noble cowboy-soldiers in the mold of George Armstrong Custer and Theodore Roosevelt. This model would become enshrined in the national consciousness by Western movies starring John Wayne and other cowboy heroes.

Meanwhile, we had to demonize the Indians so we had a "valid" reason to kill them. So we folded them all into a single set of Plains chief and warrior stereotypes. Because acknowledging that many tribes had signed treaties and were at peace with the US didn't fit the national narrative. And we started to demonize Indians with terms like "dirty," "thieving," "ragged," "degenerate," "vile," "bloodthirsty," and "murderous." Words that may have been neutral, like "redskin" or "squaw," started to become epithets.

Propaganda needed to prosecute war

The public had been divided on the Indian issue. The Indian Removal Act had passed by only one vote, and people were appalled at some of the Army massacres. The Nazi-style propaganda campaign swung public opinion against the Indians--just as it did the Jews half a century later. It made extermination seem like a sad but necessary choice.

Even artists (authors, poets, painters) who were usually sympathetic to the underdog chimed in with paeans to the vanishing Indian. The liberal/romantic/sentimental view was that Indians were doomed to disappear as a result of inevitable "natural" forces. The conservative/pragmatic/business position was that we had to get rid of the Indians by hook or crook.

Almost no one took the position that, hey, the Indians were here first, had a valid way of life, and signed treaties to guarantee their rights. Maybe we could practice what we preach and treat them with Christian kindness rather than destroy them as devils. You know, give them part of the country and coexist with them rather than kill them and take everything they own.

How the extermination was carried out:

In case the media back East got wind of such atrocities, Sherman promised Sheridan that he would run interference against any complaints: “I will back you with my whole authority, and stand between you and any efforts that may be attempted in your rear to restrain your purpose or check your troops.” [Fellman’s Citizen Sherman]

Sherman and Sheridan’s troops conducted more than one thousand attacks on Indian villages, mostly in the winter months, when families were together. The U.S. army’s actions matched its leaders’ rhetoric of extermination.

As mentioned earlier, Sherman gave orders to kill everyone and everything, including dogs, and to burn everything that would burn so as to increase the likelihood that any survivors would starve or freeze to death.

The soldiers also waged a war of extermination on the buffalo, which was the Indians’ chief source of food, winter clothing, and other goods (the Indians even made fish hooks out of dried buffalo bones and bow strings out of sinews).

Genocide is as genocide does

This puts the lie to everyone who has claimed genocide wasn't an "official" American policy. Sure, Congress didn't pass a Kill the Indians Act, but who cares? The people in charge--Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, et al.--established US policy by their words and deeds.

They didn't need to pass a law to launch the Indian Wars. They did it by executive decisions and military orders. And their intent was plain: to figuratively or literally exterminate the Indians. To clear the land for railroads, ranchers, miners, settlers, and other "good Christian" capitalists.

For more on the subject, see:

Indian in the Living Room

Muslims killed thousands, Christians didn't?!

Review of Waterbuster

Tim Wise on Ward Churchill

America is Ground Zero to Indians

Etc.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.