The Director of the Indian Museum Says It’s Time to Retire the Indian Motif in Sports

On February 7, joined by a panel of ten scholars and authors, Gover will deliver opening remarks for a discussion on the history and ongoing use in sports today of Indian mascots.

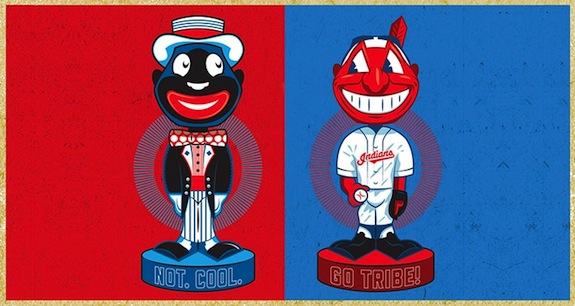

Though many have been retired, including Oklahoma’s Little Red in 1972, notable examples—baseball’s Cleveland Indians and Atlanta Braves, and football’s Washington Redskins—continue, perhaps not as mascots, but in naming conventions and the use of Indian motifs in logos.

“We need to bring out the history, and that’s the point of the seminar, is that it’s not a benign sort of undertaking,” explains Gover. He’s quick to add that he doesn’t regard the teams’ fans as culpable, but he likewise doesn’t hesitate to call out the mascots and the names of the teams as inherently racist.

At the symposium

Redskins name change demanded at Smithsonian forum

By Annys Shin

The speakers took issue with the standard defense offered by past Redskins owners that the name is a way of honoring Native Americans.

“Honors like that we don’t need,” said Robert Holden, deputy director of the National Congress of American Indians.

The name was intended to honor one man, former head coach William “Lone Star” Dietz, said Linda Waggoner, a lecturer at Sonoma State University in California. As the story goes, in 1933, co-owner George Preston Marshall renamed the then-Boston Braves the Redskins after Dietz, who adopted the identity of a Lakota man as part of his persona. The Redskins name followed the team to Washington.

Waggoner said Dietz may not have been Sioux at all but initially passed himself off as so to avoid military service.

Several speakers discussed how demeaning the term is considered. Manley Begay recalled being taunted as a “dirty redskin.”

“Those words have stayed with me,” said Begay, co-director of the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development and one of the plaintiffs in a 1992 lawsuit challenging the Redskins trademark.

Patrick Pexton: Listening to Native Americans

By Patrick B. Pexton

Meanwhile, on Jan. 28 The Post pulled from publication a short high school sports story about the girls swim team at Holton-Arms School in Bethesda, the Panthers. It was held because the photo that went with the story showed the girls, who dress in a different theme each meet to encourage team spirit, wearing face paint and feathers—seemingly Native American warrior garb.

Wearing face paint and feathers, many Native Americans feel, is a taking of their cultural and religious traditions. The paint and feathers have distinct meanings for each tribe and nation, and they often are worn only because an individual has earned them through tests, deeds and ceremonies of which white culture has little knowledge or appreciation.

The best analogy I could come up with is the way we treat U.S. military uniforms and insignia. It is against federal law for a civilian to wear the uniform of a U.S. soldier, sailor, airman or Marine for personal gain. Similarly, within the military, if you wear a medal or insignia that you didn’t earn, it is a crime under military law.

“Every major national Native American organization has declared that the name of the pro football team in our nation’s capital is the most offensive thing native peoples can be called in the English language and has called for it to be changed,” she said.

“It’s okay if others aren’t offended by it,” she added. “They should respect that we are offended and that this is something they can do something about—in our world where we can do little about most things, this is something we can actually do something to fix. They should care about it even a tiny bit because we care about it so much.”

By Dave Zirin

Despite repeated requests from the museum, the Redskins refused to send anyone to make the case publicly that the name is anything other than a self-evident slur. Like their owner, the ham-fisted, rabbit-eared Dan Snyder, they celebrate the moniker only when no one is present to challenge them. Since purchasing the franchise in 1999, Snyder has maintained that the name "Redskins” was a “tribute,” as former team Vice President Karl Swanson said, “derived from the Native American tradition for warriors to daub their bodies with red clay before battle.” This is not an argument they felt confident making at the Smithsonian because the laughter would have cracked the Capitol dome. The team name was the brainchild not of an anthropologist who advised on the fierce honor of the “red-clay warriors” but of team founder, segregationist and Dixiecrat George Preston Marshall.

Senator Campbell said that he asks people, “How would you feel if the team was called the Washington Darkies?” George Preston Marshall would have felt euphoric because he adored minstrel shows and fetishized the confederacy. As Thomas G. Smith wrote in his book Showdown: JFK and the Integration of the Washington Redskins, when Marshall proposed marriage to his future wife Corrine, he did so “amidst fragrant honeysuckle while a group of African American performers [dressed like house-slave extras from Gone with the Wind] sang ‘Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,’” a song that speaks lovingly of how slaves love to see affection between their “Massa and Missus.” The Redskins were named for the minstrelsy Marshall adored and, as the southernmost team in the league at the time, to appeal to Dixie. They were also, surprise, the last team in the NFL to integrate.

If you know this background, it’s risible to hear NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell say, “I think Dan Snyder and the organization have made it very clear that they are proud of that name and that heritage, and I think the fans are, too.” There is nothing to be proud of in this “heritage,” unless your tastes tend toward the antebellum South. In a league that’s 70 percent African-American yet couldn’t seem to find any coaches or executives of color to hire this off-season, the Redskins are also a reminder, as William Faulkner wrote, that “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Note that I compared wearing headdresses to medals in Hipster Medals Instead of Headdresses. Glad to see someone else recognized the validity of the comparison.

For more on the Washington Redskins, see Rob Quoted on Washington Redskins, Indians Are "Whiners," Not Warriors? and "Redskins" Approaching a Tipping Point?

1 comment:

For more on the subject, see:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/dc-sports-bog/wp/2013/02/25/notah-begay-calls-redskins-nickname-institutionalized-degradation/

Notah Begay calls Redskins nickname ‘institutionalized degradation’

“If you ask me, it is offensive,” Begay said midway through the segment, when asked about the Redskins name. “And I think it’s just a very clear example of institutionalized degradation of an ethnic minority, that being the Native American people. To classify it as simply a matter of political correctness only seeks to trivialize it a little bit, to an extent that it undermines the very human foundation of the people itself. I mean, if you look further and deeper into the issue, it’s about the culture, it’s about the identity, it’s about the history of our people. And that in and of itself is something that I think needs to be looked at further.

“I don’t ever see myself going to a Redskins game,” he continued. “Or I should say, if I were to take my kids to a Redskins game, and we were to see a non-native dressed up in traditional regalia, with eagle feathers in a headdress, dancing around, basically mocking the culture and the tradition, it would be very difficult to explain to my children. And not only to my children, but children of many families across this country. I mean, this country was founded on the premise of equality and human rights and civil rights, and I don’t know at what point we decide what our tolerance levels are for discrimination. And who gets to decide? I think that’s the compelling question here, is who gets decide what is discriminatory and what isn’t?”

Post a Comment