Minnesota Works on Forgiving But Not Forgetting Its Native History

By Konnie Lemay

“These men fought for the Dakota way of life, trying to hang onto something, to hang onto this land for the future generations of their children and grandchildren,” Vernell Wabasha, wife of hereditary chief Ernest Wabasha, who led the move for the memorial, told the Mankato Free Press.

Dedication of the $110,000 memorial, just after the ending in Mankato that day of the Dakota Wokiksuye Memorial Ride, will wrap up a year of lectures, discussions, exhibits, newspaper articles, radio broadcasts, concerts and commemorations in the state of Minnesota acknowledging the history of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

For many in Minnesota—both Native and non-Native—the events introduced them to a dark history of their state that they had never heard.

“I don’t remember learning much about the war, certainly not the aftermath,” said Minnesota author Diane Wilson, who is Dakota. “The 38 hanged in Mankato, those were the best known facts. … The fact of the removal of the Dakota was something that was so silent, especially that forced march of the 1,700 elders, children and women.”

Co-Opting the Memory of the Dakota 38+2

By Waziyatawi

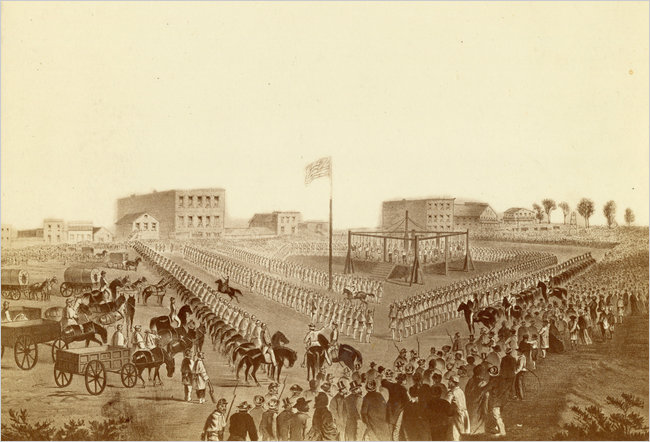

This emphasis on reconciliation at the site of the largest mass hanging from one gallows in world history (yes, it used to be listed as a Guinness World Record) illuminates a deep split within the Dakota population that remains 150 years later.

Not all Dakota people are eager to offer forgiveness to the occupiers of our homeland. The crimes of genocide, ethnic cleansing and land theft are too great for time alone to heal. Furthermore, the injustices continue through the ongoing occupation of our homeland, the diaspora and exile of our people, the denial of our rights to religious freedom including access to sacred sites, the lack of access to traditional foods, the theft of our children, the mass incarceration of our population, the imposition of colonial systems and institutions on every aspect of our lives and the daily exploitation and destruction of our homeland. In 1862, Dakota warriors fought to defend our land, our people and our way of life. Thirty-eight of them were hanged in 1862 as a consequence of their resistance to occupation and two more were hanged in 1865. But the struggles remain the same today and we are still in need of warriors to achieve justice and liberation for our people.

The vision of the horse ride in honor of the 38+2 began with Jim Miller, a Lakota Vietnam veteran. He determined it was about peace, healing and reconciliation. That is, he came to Dakota people with a message about how our resistance fighters should be honored. Imagine if a Dakota person had a vision about how Crazy Horse or Sitting Bull should be honored, brought that vision to Lakota people, and then determined the honoring should be about peace and reconciliation. I hardly think such a vision would be embraced by our western relatives. Unfortunately, some Dakota people have followed his vision and the result is an absurdly extreme position (“forgive everyone everything”).

Furthermore, in all the media coverage surrounding the horse-ride memorial, it is not clear why they are honoring the 38+2. The prominence of forgiveness, healing and reconciliation in the rhetoric of the horse riders is what would better be associated with the “cut-hair,” “friendly” or Christian Indians who sided with the whites in 1862—the people who were considered traitors by Dakota standards. The message of peace and forgiveness would make sense if the riders were honoring those ancestors. It is not what one would associate with the 38 men hanged at Mankato or Wakanozanzan and Sakpe hanged at Fort Snelling. Far from being advocates of peace and reconciliation, they were Dakota men who took up arms because they believed in the righteousness of our struggle

Of course, the monument's creators might say they believe in forgiving but not forgetting. But forgiving, like apologizing, is a useless gesture without some accompanying action. What are the creators doing to ensure Native rights and justice now?

Forgiving also aids the process of forgetting. "Remember the Mankato 38?" someone might ask. "Why should we? I thought the Indians forgave us for that back in 2012. That means it's over and done with."

The real-world choice is often forgiving and forgetting or not forgiving and not forgetting. Needless to say, I prefer the latter.

For more on the Mankato 38, see Mankato 38 Art Exhibit and Mankato Concert to Mourn Dakota War.

No comments:

Post a Comment