Photographer Jimmy Nelson is just the latest artist to act like indigenous groups are about to die out

By Elissa Washuta

The Māori people, featured in Nelson’s book, make up 15 percent of New Zealand’s total population, and the 2012 census estimate of 682,100 Māori residents is part of a consistent upward trend. Seven seats of the Parliament of New Zealand are designated as Māori. Their communities have been impacted by colonization and the resulting warfare, disease, land loss and assimilation. But, although contact brought changes, far from being erased, the Māori people continue to thrive.

Nelson approached his subjects with a predefined notion of indigenous authenticity, which doesn’t align with the realities that have faced indigenous communities since time immemorial. In an interview with CNN.com, Nelson says that he grew up in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Gabon and Cameroon, and feels that Africa “has lost the majority of its ethnicity and authenticity. … [W]hat I saw in my childhood is not there anymore.” Similarly, Nelson told Time that he chose to leave out North American tribes because they haven’t retained their heritage. To critique the “authenticity” of another culture from the outside is a dangerous practice, and Nelson’s evaluation of communities during his lifetime fails to account for the flux experienced over thousands of years. Too often, onlookers expect indigenous peoples to remain static for the entirety of their existence, failing to consider their long histories of change before contact with outsiders.

The questioning and judgment of indigenous authenticity often have their roots in appearance. By treating people as art, Nelson plays into this notion. In his photos of the Kalam people of Papua New Guinea and Indonesia, headdresses, necklaces and body ornamentation serve as visual representations of identity. Besides Nelson’s written descriptions of each group he photographs, visual cues are all we can use to form our understanding. He calls himself a “collector of truth,” but how much truth can fit into a work rendered in two dimensions, telling visual stories curated by an outsider? Personal strongholds of identity are often invisible.

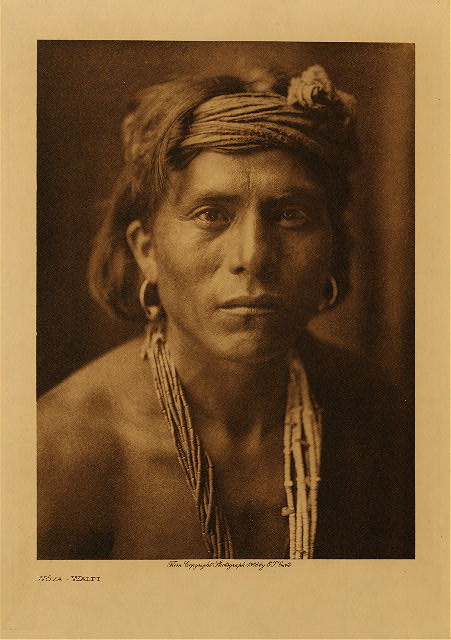

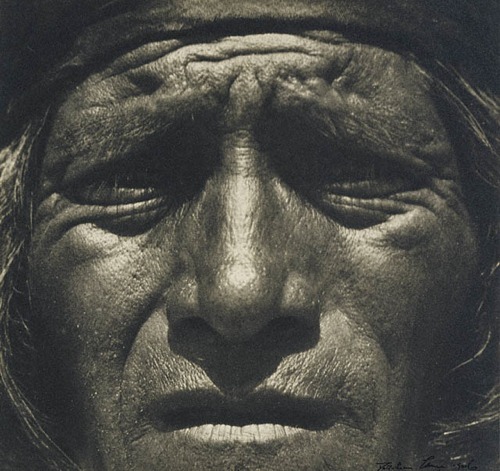

Nelson’s publication of “Before They Pass Away” is reminiscent of Edward S. Curtis and his series “The North American Indian.” Beginning in the 1890s, Curtis took more than 40,000 photographs of North American Native peoples. While Curtis has been celebrated for his visual documentation of peoples and ways of life that are said to be gone, he is criticized for his manipulation of shots and subjects. Around 1910, he retouched a photo of Little Plume and his son Yellow Kidney, two Blackfoot men, to remove an alarm clock Curtis thought to be inconsistent with the otherwise traditional image.

In interviews, Nelson frequently cites Curtis as an inspiration for his work. Curtis’s posing of his subjects is treated as a scandal, but Nelson freely admits to the New York Times, “I directed the majority of the pictures, which Curtis also did.” While the people Curtis photographed often appear in their finest ceremonial attire, Nelson continues, “And 80 percent of the people I photographed are dressed as they do daily. About 20 percent are in their Sunday best.”

Curtis made significant contributions to the tribes he photographed by documenting points in their histories. In 1910, he photographed my great-great-grandmother’s half-sister, Virginia Miller, or Whylick Quiuck, with her canoe. He also recorded her account of the hanging of her father, Tumalth of the Cascades, by the U.S. government. Just a year earlier, the young Cascade chief added his signature to the Kalapuya Treaty of 1855. Virginia’s story of false accusations that led to her father’s death would have been lost without Curtis’s documentation. This is an important piece of the history of the Cascade people and of my family.

Although Curtis’s body of work stands as a contribution to tribal histories, he may have done just as much to further the notion of Native peoples as a vanishing race. According to Timothy Egan’s recent Curtis biography “Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher,” in 1907, Curtis wrote in a photo caption, “The thought which this picture is meant to convey is that the Indians as a race, already shorn of their tribal strength and stripped of their primitive dress, are passing into the darkness of an unknown future.” Of the Hopi, he wrote, “There won’t be anything left of them in a few generations and it’s a tragedy.” More than a hundred years later, the Hopi people continue to live in Hopituskwa, where they have retained their culture, religion and language.