Like the present, the past is alive with controversy.

By James W. Loewen

Sometimes the pressure to conform to this convention has been so strong that it muddles the stories artists seek to tell. Facing west from the Iowa State Capitol in Des Moines are three figures titled The Pioneers. The artist meant them to represent a “father and son guided by a friendly Indian.” But such is the power of hieratic scale that the sculptor has shown the Indian seated subserviently looking off to the side, while the white man stands gazing capably ahead. No visitor would guess that the Indian was meant to be the guide of the group.

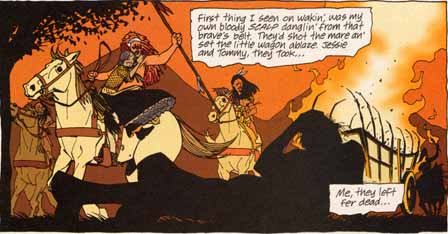

And that’s a shame, because the historical commonplace of Indian as guide to westering pioneers is a concept not very familiar to most Americans. We’ve all been influenced by the archetype of the whooping Indians riding around and around the wagon train, circled for protection. It turns out that this scenario probably never happened either—even once. Of course, a moment’s thought makes evident its silliness: Why would anyone ride around and around, trying haplessly to fire accurately from his bouncing steed, while presenting such a tempting broadside target to John Wayne, lying prone with both elbows braced for best aim?

In reality, Indians rode around and around because they were in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and its many imitators, and they were performing in circus tents. Circus tents are round. In the real West, not only did Indians not ride around and around, they were much more likely to make money off the newcomers by selling them fish, helping them ford the river, or, as in Des Moines, hiring on as guide. But we don’t learn that from most movies—or from most historic sites.

No comments:

Post a Comment