By Jack Rooney

Fryberg’s lecture, titled “From Stereotyping to Invisibility: The Psychological Consequences of Using American Indian Mascots,” highlighted several studies she and her colleagues have performed.

“Consistent with the past two studies, it turns out that being exposed to any one of these mascots decreased achievement-related possible selves,” she said. “So what it means is if they saw the Indian mascot, then any possible selves they had related to achievement in school were depressed.”

Indians and blacks too

Some related research on stereotypes:

Stereotype Threat Widens Achievement Gap

Steele and Aronson gave Black and White college students a half-hour test using difficult items from the verbal Graduate Record Exam (GRE). In the stereotype-threat condition, they told students the test diagnosed intellectual ability, thus potentially eliciting the stereotype that Blacks are less intelligent than Whites. In the no-stereotype-threat condition, the researchers told students that the test was a problem-solving lab task that said nothing about ability, presumably rendering stereotypes irrelevant. In the stereotype threat condition, Blacks--who were matched with Whites in their group by SAT scores--did less well than Whites. In the no stereotype- threat condition--in which the exact same test was described as a lab task that did not indicate ability--Blacks' performance rose to match that of equally skilled Whites. Additional experiments that minimized the stereotype threat endemic to standardized tests also resulted in equal performance. One study found that when students merely recorded their race (presumably making the stereotype salient), and were not told the test was diagnostic of their ability, Blacks still performed worse than Whites.

Spencer, Steele, and Diane Quinn, PhD, also found that merely telling women that a math test does not show gender differences improved their test performance. The researchers gave a math test to men and women after telling half the women that the test had shown gender differences, and telling the rest that it found none. When test administrators told women that that tests showed no gender differences, the women performed equal to men. Those who were told the test showed gender differences did significantly worse than men, just like women who were told nothing about the test. This experiment was conducted with women who were top performers in math, just as the experiments on race were conducted with strong, motivated students.

"Surprisingly, you don't have to believe in the stereotype to be vulnerable to it," he pointed out to his audience at the APA convention.

"Everyone in a collective knows the stereotypes about a given target group, including the group members themselves, and everyone knows that everyone knows," Steele wrote in a paper prepared for the convention. "Thus the predicament of 'stereotype vulnerability': The group members then know that anything about them or anything they do that fits the stereotype can be taken as confirming it as self-characteristic, in the eyes of others, and perhaps even in their own eyes. This vulnerability amounts to a jeopardy of double devaluation: once for whatever bad thing the stereotype-fitting behavior or feature would say about anyone, and again for its confirmation of the bad things alleged in the stereotype.

How would that relate to my experience in the 21st century? Try harder and I can be a dirt-poor farmer too?

If a school had a program that honored real live Natives, that might be different. But few if any schools have that.

This point could generate a whole article. An article ripping the idea that centuries-old images are supposed to help Natives in general and Native students in particular.

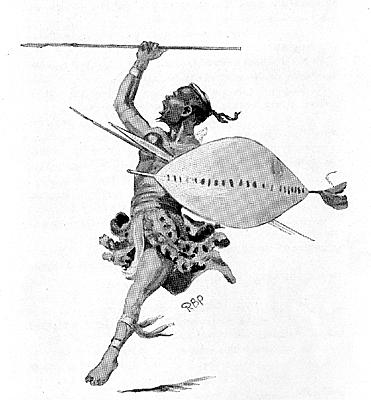

It obviously wouldn't work if you showed black students pictures of half-naked African spearchuckers. How exactly is the Native case different?

Be all that you can be, African Americans! Aim for the stars!

Anthropological Association Takes a Stand in Native American Mascot Debate

By Rob Stott

Anthropologists have joined a long line of groups to call on professional and college sports communities to rethink their use of Native American mascots and nicknames. Except in instances where tribes or key stakeholders have been consulted (see Florida State University and San Diego State University), sports organizations should “denounce and abandon the use of American Indian” imagery, the American Anthropological Association said in a statement [PDF] released last week.

“While these organizations may feel they are honoring Native Americans, many in that community view it to be a degrading and painful symbol of racism,” Monica Heller, AAA president, said in the statement. “Research has established that the continued use of American Indian sports mascots harms American Indian people in psychological, educational, and social ways. Frankly, I don’t see where the honor is in that.”

No comments:

Post a Comment