By Associated Press

A U.S. Army force led by Col. John M. Chivington (SHIV'-ing-tin) swept into a sleeping Indian village along Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado on Nov. 29, 1864. Troops killed more than 160 Cheyenne and Arapaho, most of them women, children and the elderly. Officials at the time insisted the attack was to avenge Native American raids on white settlers and kidnappings of women and children.

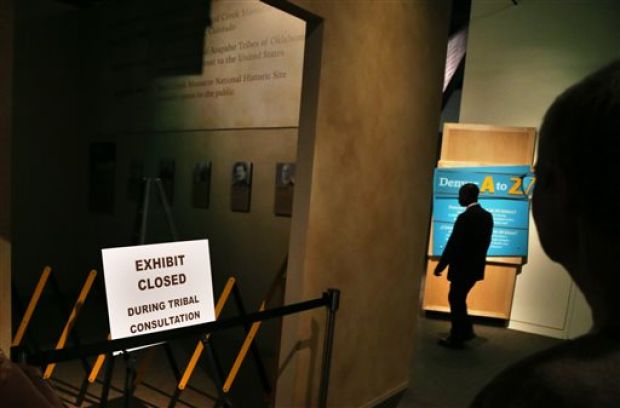

Dale Hamilton, a descendant of Chief Sand Hill, one of the survivors, said curators of the History Colorado Center museum in Denver didn't consult tribes about the display, which opened in April 2012. The exhibit was closed in June.

Tribal historians found some dates were wrong, excerpts from letters left out crucial details, and the exhibit attempted to explain Native American-white settler conflicts as a "collision of cultures," claimed Hamilton, of Concho, Okla., where he lives with Cheyenne and Southern Arapahoe tribes.

"This wasn't a clash of cultures. This was a straight-up massacre. All we are looking for is respect for our relatives who were murdered," said Hamilton.

By The Denver Post Editorial Board

The clear lesson from this episode is that museum officials should have reached out earlier to the tribes and given them fuller opportunities to voice their concerns.

And their concerns, outlined in reporting by Westword's Patricia Calhoun over the last several months, were many.

First, the very name of the exhibit, "Collision: The Sand Creek Massacre," was offensive to many tribal members, who believed the event was being portrayed as an inevitable clash of cultures rather than an indefensible massacre.

No comments:

Post a Comment