Trudell: The politics belong to somebody else so it's likely to never synchronize with us; but again, our culture and our art--that's us. That's the reality of who we are, and it is only through this way that we can truly speak our truths. We couldn't do it through the politics because you had to compromise your truths or deny them to get things done. But through our culture and our art we can speak our truths. We can express the reality of who we are and how we feel and how we see. And this communication and expression of reality I think is very important for us collectively as a people because it is some kind of a bonding. It's some kind of a joining, communion almost in a way.

7 comments:

You must be smarter than the average bear, Russ.

I've always argued that the media (Wild West shows, dime novels, Western movies, Dances with Wolves, Pocahontas, mascots, etc.) have had a profound effect on how we viewed and treated Indians. That's why I've focused on writing stories and creating comics rather than carrying signs or marching in the streets.

But note that Trudell does say activism was a necessary step in the process. I agree with that too. I think blacks, Indians, women, et al. had to raise the nation's consciousness before Americans could treat them as equals. Once their agendas were on the table, then we could deal with them in diverse and personal ways. Some could continue organizing or demonstrating while others could run for office or work within the system for change.

Others could stand back and serve as educators and information brokers for those on the front lines. That's what I've chosen to do by disseminating news (PECHANGA.net), analyzing issues (this website and blog), and telling stories (PEACE PARTY).

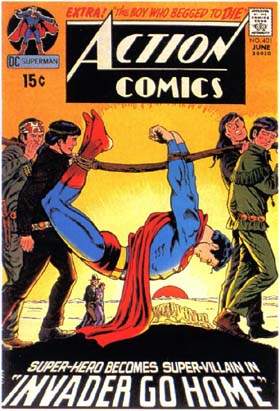

I'm glad your friends remembered the plot, because I didn't. I would've thought you could find a summary of ACTION #401-402 via Google, but a quick search didn't turn up anything.

And what a lame-sounding plot, too. You can be sure that any comic with "mole machines" automatically sucks. ACTION started to decline in quality a couple years earlier and this two-parter continued the trend.

I guess they called the Indians "Navarro" because they were too chicken to call them Navajo. I've written about the problem of using fictional tribes before--e.g., in Wingfooting It with Wyatt. In my stories, I'm not afraid to call real tribes by name.

Another quick search suggests the price for these comics might range from maybe $3.00 in fair condition to $10.00 in near mint condition. So they're not totally out of reach if you want to collect them.

Wyatt Wingfoot first appeared in FANTASTIC FOUR #50 (May 1966). Stan Lee created him and the Keewazi tribe. Later writers merely perpetuated the problems Lee introduced by using a fictional tribe.

Using a fictional tribe may be necessary occasionally for technical or legal reasons I don't quite understand. It's never good, but sometimes it may not cause much harm. In other words, it may be tolerable if not beneficial.

The "Three Nations Reservation" in Edge of America is a good example of a fictional Native nation that does little harm. It's located in Utah near the Ute, Paiute, and Navajo reservations, so a combined reservation is plausible. The movie doesn't delve into the tribe's history or culture, so there's no need to invent those things. As far as I can tell, all the bits of language and culture are Navajo, so one can pretend that Three Nations is essentially Navajo.

Marvel's Keewazi tribe has a few unique problems. One, it's a super-scientific culture that's pretending to be poor and backward, which raises a host of questions. The whole history of American Indians is bogus if a tribe like the Keewazi exists. Two, the comics eventually delve into Wingfoot's ancestry. They link him to his grandfather's mystical powers and various made-up myths.

Look at the illustration on my Winging It with Wyatt page. It shows a mixture of Pueblo dwellings and a Navajo hogan. Since the Keewazis have no real culture, the creators thought it was okay to jumble together these unrelated constructs.

The result? Readers learn there's no difference between the Keewazi, the Pueblos, and the Navajo. All the tribes in the American Southwest might as well be the same. Conflicts like the Hopi-Navajo land dispute can't exist because they're one big happy family.

Fictional countries and ethnic groups are almost always less than good. Go to my Wyatt Wingfoot postings and read my arguments there, because I don't have time to repeat them here.

The short version is that the fictional nations are usually in Latin America, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, or Africa. Or they're in the middle of the US, if they're Indian nations. But you never see a fictional US state or English-speaking country. Basically, real nations are members of the West or the "First World" while fictional nations aren't.

Why is, say, a fictional African country okay but not a fictional US state? Because African peoples, cultures, and geography aren't real to us. We don't care if some comic-book creator jumbles them together and makes a mess of them. All African countries are pretty much the same, right? They have corrupt governments, armed militias, colorful marketplaces, cattle-herding tribes, witch doctors, and jungle animals...right?

The same applies to Indian tribes. If they're not real, you can characterize them with a few basic stereotypes. You don't have to deal with the complex history and culture of each individual tribe. In fact, doing this denies their individuality. It makes them into one homogenized and undifferentiated mass of people.

As for the Cherokee, I'm well aware that they have casinos. I work in the Indian gaming industry, remember.

But how wealthy is wealthy? Oklahoma has almost 100 casinos competing with each other, so no tribe is doing as well as those in Connecticut or California. These casinos tend to be truck-stop bingo halls rather than destination hotel-resorts with concert halls and golf courses.

Moreover, Oklahoma's tribes have large population bases, so they aren't earning as much per capita. Their gaming income has to go to fund a lot of social services for a lot of people.

In gaming articles and at gaming conventions and, no one refers to Oklahoma's tribes as wealthy. A review of a 2001 report on Indian gaming revenue shows that the tribes in California, Connecticut, Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, Washington, Arizona, Florida, New Mexico, Oregon, and New York earned more than Oklahoma's tribes. So until I see further evidence, I'll stick with my claim. Oklahoma's gaming tribes may be comfortably middle-class, but they're not rich.

Using a fictional tribe would've solved the problem of bastardizing the Tlingit culture, but it would've introduced the problem of simplifying and homogenizing diverse Indian cultures. The best solution would be to 1) learn the Tlingit culture well enough to depict it accurately, or 2) get a Tlingit co-writer or Tlingit advisers to help you with it.

Alternatively, Mikaelsen could've said the Indian was a "mixed breed" from several tribes who was using a combination of cultural techniques. Unless his goal was to make some point about Tlingit culture, there was no need to use the Tlingits or any particular culture.

The goal of Touching Spirit Bear seems to have been a generic study of Northwest Indian banishment techniques, so a generic NW Indian would've sufficed. Making him Tlingit didn't do anything except prove Mikaelsen didn't know the Tlingit culture.

In summary, writers, make your Indians as specific as they need to be for the story, but no more. If the story requires characters who are more specific than you're able to create, don't change (simplify) their culture to fit the story. Change the characters or the story instead.

Post a Comment