By Richard Prince

When asked why, attendees offered remarkably similar responses, variations of, "Welcome to my world. Native Americans receive unequal justice all the time."

"We have our own system of injustice, and we've been living it for 100 years," Tim Giago, Oglala Lakota, veteran Native journalist and founding president of NAJA, told Journal-isms.

"We're used to it. We have to prove our innocence," replied Lucinda Hughes-Juan, Tohono O'odham, a freelance business writer and business instructor at Tohono O'odham Community College.

"Native Americans have always dealt with similar circumstances," said Ronnie Washines of the Yakama Nation Review, a Yakama and a former NAJA president.

Each could cite examples.

In South Dakota, Giago said, a Native American was given a five-year sentence for driving while intoxicated, while a white man received probation.

"On my reservation alone," Washines said, "there have been almost a dozen unsolved murders and missing women cases." Then-Attorney General Alberto Gonzales came to the reservation and promised to have investigators review all of the unsolved homicide and mysterious death cases on the reservation.

"They can't find anything. Came back with zero," Washines said.

"This is typical," Hughes-Juan said of the way justice was administered in the Martin case. "Being followed around in stores, stuff like that. We have so many issues, poverty issues, day-to-day survival."

Outside the convention, some Native Americans have taken a different approach. Activist Suzan Shown Harjo last year used the Martin case, in which Zimmerman, a night watchman, fatally shot Martin, an unarmed black teenager, as an example of white privilege.

"All sorts of excuses are made for whites who harm non-whites, mainly that they act out of fear," Harjo wrote. "No one really acknowledges what their fear is: That non-whites, once in charge of anything, will be as bad to the whites as they have been to us."

Suzette Brewer wrote last week for the Indian Country Today Media Network about a high-profile custody case involving 3-year-old Veronica Brown, a Cherokee, and Matt and Melanie Capobianco, a white couple who took the newborn Veronica home from the hospital in an open adoption approved by the mother. Brewer quoted an outraged Native legal scholar: "This is Indian country's Trayvon Martin moment; we cannot pass on this."

Gyasi Ross, a member of the Blackfeet Nation whose family also belongs to the Suquamish Nation, wrote last year about the backlash he received from "one small group of dissenters" who disagreed with his piece urging everyone to care about the Martin case.

"We must realize that Native people have a vested interest in making sure that everybody in this country's rights are respected," Ross wrote. "The more that all people of color are able to enforce their rights in this country, the more likely that justice will eventually make its way to Native people.

"We are all inextricably linked and need each other--therefore, Indian people should be screaming for justice for Trayvon Martin specifically because we've seen many instances of Native people being killed by rednecks under the theory that the Native people were 'threatening' before.

Cicero's Tongue: “Hey! It’s me, Trayvon!”

By Vorris L. Nunley

Trayvon the person, the human being, rarely entered the courtroom. The defense was unwilling to skirmish with the Trayvon invented by Zimmerman: Trayvon as King Kong in a hoodie: savage, undomesticated, prone to violence, guilty by definition; George Zimmerman as Fay Wray: fragile, scared, driven to self-defense, innocent through skin. The prosecution tapped into the galvanizing energy of the Black trope with such brio that the defense lawyers seemed to be Moot Court scrubs. The misbehaving Black body (that is, any Black body challenging White notions of proper Black civility and decorum in fact or in fearful projection) is by definition wrong, needing to be quelled and made to behave, often by calling the police to say how “scared” they were, how they feared for their safety.

How the System Worked: The US v. Trayvon Martin

By Robin D. G. Kelley

The list is long and deep. In 2012 alone, police officers, security guards or vigilantes took the lives of 136 unarmed black men and women—at least twenty-five of whom were killed by vigilantes. In ten of the incidents, the killers were not charged with a crime, and most of those who were charged either escaped conviction or accepted reduced charges in exchange for a guilty plea. And I haven’t included the reign of terror that produced at least 5,000 legal lynchings in the United States, or the numerous assassinations—from political activists to four black girls attending Sunday school in Birmingham fifty years ago.

The point is that justice was always going to elude Trayvon Martin, not because the system failed, but because it worked. Martin died and Zimmerman walked because our entire political and legal foundations were built on an ideology of settler colonialism—an ideology in which the protection of white property rights was always sacrosanct; predators and threats to those privileges were almost always black, brown, and red; and where the very purpose of police power was to discipline, monitor, and contain populations rendered a threat to white property and privilege. This has been the legal standard for African Americans and other racialized groups in the U.S. long before ALEC or the NRA came into being. We were rendered property in slavery, and a threat to property in freedom. And during the brief moment in the 1860s and ‘70s, when former slaves participated in democracy, held political offices, and insisted on the rights of citizenship, it was a well-armed (white) citizenry that overthrew democratically-elected governments in the South, assassinated black political leaders, stripped African-Americans of virtually all citizenship rights (the franchise, the right of habeas corpus, right of free speech and assembly, etc.), and turned an entire people into predators.

By Mark Karlin

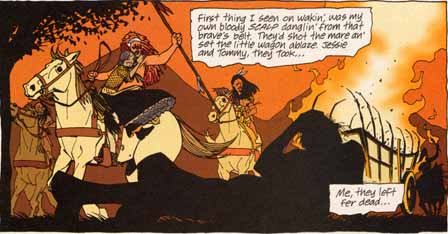

Historically, if we go back to the founding and expansion of what is now the United States, if there had been a legal entity existing at that time, Native Americans (as the illustration for this article points out) would have been entitled to stand their ground against the colonizers from Europe who were stealing their land and massacring them.

We would be subject to Native American law right now if indigenous tribes had had the enforced right to stand their ground as European conquerors expanded westward, creating what is now the United States.

There would have been no development of the Southern tyranny and abomination of slavery, which imported Africans as property and the source of wealth for aristocratic plantation owners.

There would have likely, ironically, been no "Stand Your Ground" laws aimed at de facto allowing the murder of non-whites as BuzzFlash at Truthout wrote about in a July 6 column, "It's Not Just George Zimmerman on Trial, It's America's Acceptance of Killing 'the Other'."

No comments:

Post a Comment