By Joanna Eede

In attributing other-worldly qualities to nature, however, and in seeing them as sacred spaces where God lives but man must not, ideas developed which were arguably at the root of conservation policies. "For decades, the idea of 'wilderness' has been a fundamental tenet of the environmental movement," wrote the historian William Cronon. Such policies adversely affected the indigenous tribal peoples for whom such "wild" places were merely "home."

Today there are an estimated 120,000 protected areas worldwide, covering nearly 15% of the world's land surface. Conservation is undoubtedly vital when the biological diversity of the planet is so threatened. But the sorry backdrop to these statistics--the story that is overlooked in the desire to preserve the "wild"--is one of intense human suffering. For in the creation of reserves, millions of people--most of them tribal--have been evicted from their homes.

There may also be room for a broader cultural objective; one which lies in reshaping the popular idea of "wilderness" in western thinking, by acknowledging the ancient interrelationship of man and the natural world. For destructive attitudes are born partly of dualistic ideas; in emphasizing the separateness of man and nature. "Any way of looking at nature that encourages us to believe we are separate from it is likely to reinforce irresponsible behaviour," says William Cronon. The world's tribal peoples still intuitively grasp this symbiotic relationship better than most; in the words of Davi Kopenawa, "The environment is not separate from ourselves; we are inside it and it is inside us."

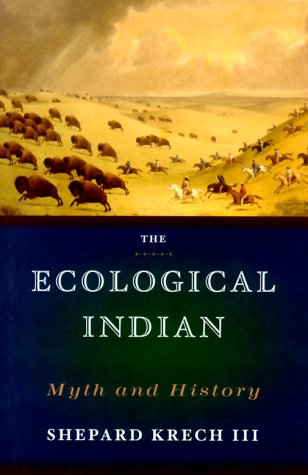

For more on national parks, see Indians Left Out at National Parks, Before There Were Parks, and Maasai Evicted Like Indians. For more on Indians' relationship with the environment, see What a Native Utopia Looks Like, Natives Understand Nature's Value, and Dennis Prager and The Ecological Indian.

No comments:

Post a Comment