This is as it should be--a giant step toward decolonization or decolonialization. It’s a step taken over recent years by the Sicangu Lakota, who had been known for so many years as the Rosebud Sioux; and those known as Pima are now Tohono O'odham, the Desert people, as they called themselves from time immemorial. And the people of Winnebago are once again the HoChunk, and the Omaha have reclaimed the traditional spelling U-Mo'n-Ho'n.

We must ask ourselves, why was it that the Europeans especially wanted to change the tribal or clan names of the peoples they encountered in the New World, and on all other continents? Surely, it wasn’t just the inability of the European invaders to spell the names so the indigenous peoples and their landmarks could be recorded in their reports back home.

Why was the highest mountain on planet Earth renamed from its Tibetan name of Qomlangma to Mount Everest, after an obscure 19th Century Surveyor General of British colonial India? Or why was Denali Peak, which was named for the Athabascan people of Alaska renamed McKinley, after the 25th President of the United States? What does it signify to them? Conquest? Possession? Superiority?

To force Indian nations to take on an alien tribal name in English was cruel enough; but often the tribe had to take the name of the military outpost that was built to keep them in virtual bondage. Fort Sill Apache; Fort Peck Assiniboine-Sioux; and Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold, are examples. Others had to adopt the name of the Christian church imposed on their village, such as Santa Ana, San Juan, San Ildefonso, and Santa Clara Pueblos.

I'm not sure Euro-Americans renamed places as a conscious effort to "break the tribal structure." Rather, they probably didn't know or care that the Indians had their names. They probably treated the Indian names as incomprehensible noise.

Trimble's "superiority" may come closest to the mark. Americans had the racist presumption that they were the only people who mattered. That the Indians' thoughts and feelings were like a dog's: irrelevant and inconsequential.

Many Americans still think this way, as countless debates over Indian mascots and Hollywood movies prove. "We're stereotyping Indians?" they say. "Who cares? We're white people and they're not."

For more on the subject, see Renaming Mt. Diablo and Renaming British Columbia.

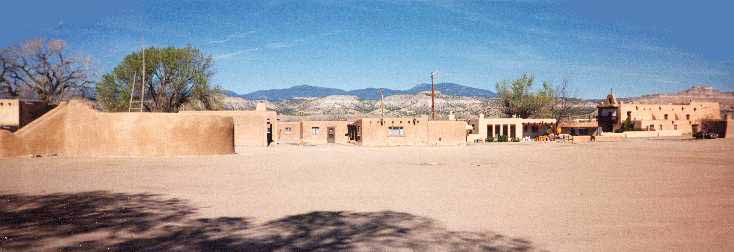

Below: The central plaza at San Ildefonso, with the round kiva at left and the old church at right.

No comments:

Post a Comment