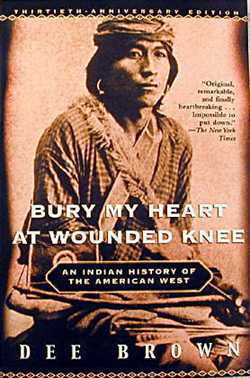

While poor Pollock could not come up with anything that vaguely resembled indigenous art, he did begin to explore native art on his own. Influenced by Henderson, he began to study Navajo sand paintings. He also began to haunt the Museum of Natural History and was fixated on the artwork of the Kwakiutl, Bella Coola, Haida, Tsimshian and Tlingit tribes. Pollock came to the realization that he was yearning for the same kind of shamanic power that these artists had achieved and began to think of his artwork as the analogy of that of tribal artists. By digging into his own subconscious and by seeking oneness with nature, he would achieve the same kind of power that he saw in the museum pieces.

It is singularly ironic that Pollock would gravitate toward American Indian artists, since fame or fortune were the last things on their mind. Pollock was simply looking for a technique that could elevate his work to a higher plane. The obsession with American Indian artwork was based on almost total ignorance about their way of life, characteristic not only of Pollock but other big-time artists and critics as well. Abstract Expressionist superstar Barnett Newman wrote in the 1947 essay "The Ideographic Picture":

"The Kwakiutl artist painting on a hide did not concern himself with ... inconsequentials...The abstract shape he used, his entire plastic language, was directed by a ritualistic will towards metaphysical understanding. The everyday realities he left to the toy-makers; the pleasant play of non-objective pattern basket weavers. To him a shape was a living thing, a vehicle for an abstract thought-complex, a carrier of the awesome feelings he felt before the terror of the unknowable."

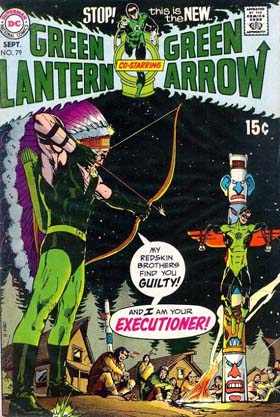

A 1946 experiment comically illustrates Pollock's running hide-and-seek with representation: over a photograph of a dog he laminated film skimmed from enamel paint. Stressed-out canines appear often. In his 1943 painting Guardians of the Secret, in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the slashingly drawn coyote-ish animal lying at the picture's bottom, between gaunt male and female hierophants, recalls the Prankster of American Indian stories.