Actors in blackface makeup are used during coverage of the World Cup. The broadcasting company says it's just a harmless spoof, but commentators say Mexico as a whole is in denial about racism.

By Tracy Wilkinson

Yes, in the 21st century, blackface characters on a major television network.

As proof, they point to the fact that slavery was ended in Mexico decades before it was abolished in the United States, and that Mexico never institutionalized racism the way the U.S. did with its segregationist laws that lasted into the 1960s.

And there is a smaller community of black Mexicans, Afro Mexicanos, many descendants of slaves first brought to the region by Spanish conquerors in the 16th century.

Often referred to by academics as the "third race" and concentrated in the coastal states of Veracruz, Oaxaca and Guerrero, they have been fighting for years for recognition as a distinct ethnic group, to be included in history books and to be given opportunities to transcend poverty.

These terms are jarring when seen through the prism of U.S. sensibilities, but here they are usually used in a context of affection and friendship.

The issue of racism in Mexico exploded a few years back when then-President Vicente Fox, in what was meant to be a defense of Mexican immigration to the United States, told a U.S. audience that Mexican immigrants were necessary because they performed the jobs that "not even blacks" wanted to do.

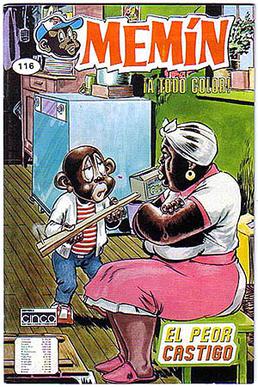

He had to apologize and receive a visit from Jesse Jackson to atone. As the furor died down, another popped up when Mexico printed postage stamps that commemorated a well-known comic-book character from the 1950s, Memin Pinguin. The character is a black boy drawn with exaggerated features. It was seen as racist by many in the U.S. who demanded Mexico withdraw the stamps; many in Mexico, including several leftist intellectuals, defended Memin Pinguin as a beloved part of Mexican culture. (Withdrawing the stamps became a moot point when they sold out within hours of going on market.)

If the "affection and friendship" defense sounds familiar, it's what Southern whites used to say about their "darkies." It's what every American used to say about Amos 'n' Andy, Aunt Jemima, and countless big-lipped Sambo characters. "We're not prejudiced against coloreds; we love them!"

Of course, this "thinking" applies directly to Indians. "We're not prejudiced against redskins, chiefs, or braves," says the typical American. "We love them so much we've made them our sports mascots."

Alas, the corollary to this thinking goes unstated. "Well, I've never met real Indians and don't know anything about them. Nor do I want to know anything about them. They're all drunks, welfare chiselers, or greedy casino owners, right? Why should I care about a bunch of degraded losers? I prefer my noble savage Indians--you know, the ones we admired for their ferocity even as we defeated them."

I don't think it would be hard to uncover this kind of unstated thinking in typical Mexicans. Ask them how they'd feel if their daughter married a "Chino" or a "Negrito." If they replied without hesitation that they wouldn't care, I'd tend to believe them. If they hesitated for more than a couple seconds, especially if they started making excuses, we could surmise their real thinking.

Were Americans filled with affection and friendship when they labeled people "micks," "wops," "spics," "Hebes," "Japs," Polacks," "greasers," "fags," "retards," and so forth and so on? Why should we believe Mexicans are any kinder when they label people? At best they're classifying people by group traits rather than seeing them as individuals. There's nothing healthy about that.

For more on the subject, see Minorities Aren't Quite American and Stereotypical Thinking Causes Racist Results.

Below: Memín Pinguín and his mammy, or how Mexicans view blacks.

No comments:

Post a Comment