Ridge sells out

In signing the Treaty of New Echota, Major Ridge's party violated the Cherokee "blood law," which prohibited the sale of Cherokee land. The arrogance of this action is hard to believe. Ridge and his people thought they knew better than the 16,000 Cherokees who wanted to stay and fight. It's not as if they knew the future; they were just guessing like everyone else.

Whatever else Major Ridge did for his people, this act seems inexcusable. If the vast majority of Cherokees wanted to commit cultural suicide, as Ridge must've thought, it was their right to do so. Ridge had no right to go against the will of his people.

According to Wikipedia, the situation was more complex than Ridge's signing a treaty behind Ross's back:

Ross' strategy was flawed because it was susceptible to the United States' making a treaty with a minority faction. On May 29, 1834, Ross received word from John H. Eaton, that a new delegation, including Major Ridge, John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and Ross' younger brother Andrew, collectively called the Ridge Party, had arrived in Washington with the goal of signing a treaty of removal. The two sides attempted reconciliation, but by October 1834 still had not come to an agreement. In January 1835 the factions were again in Washington. Pressured by the presence of the Ridge Party, Ross agreed on February 25, 1835, to exchange all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi for land west of the Mississippi and 20 million dollars. He made it contingent on the General Council's accepting the terms.

Lewis Cass, Secretary of War, believing that this was yet another ploy to delay action on removal for an additional year, threatened to sign the treaty with John Ridge. On December 29, 1835, the Ridge Party signed the removal treaty with the U.S., although this action was against the will of the majority of Cherokees.

Anyway, Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot paid the price for their actions. Assassins found them in their new homes and killed them. They didn't get fair trials, but some would call the deaths justice rather than revenge.

20-20 hindsight

Even though the Treaty of New Echota led to the Trail of Tears, it's hard to say which side was right. Not only did a quarter of the Cherokees die on the road, but things weren't calm and peaceful in the new territory. The Ridge and Ross factions continued to struggle for power. According to Trail of Tears, "Angry talk, bitter accusation, and violent reprisal flared among the Cherokee for the next 30 years."

As the narrative continues, it fell to Ross as principal chief to heal his people. To realize the continuation of a strong and sovereign Cherokee nation. By 1860, Ross managed to restore the heart of the nation. The population nearly doubled to 21,000, with the finest educational system in the US and the traditional dances honored.

Trail of Tears wants us to think removal was ultimately a success story, with the Cherokee nation reestablishing its former glory. But the contention continued during the Civil War with the Cherokees attempting neutrality, allying with the Confederacy, and returning to the Union. In the following decades, they had to deal with renewed assaults on their land, including the Dawes Act of 1887:

So was Ridge right and Ross wrong? Again, hard to say. We can only speculate on what might've happened if the Ridge Party hadn't signed the treaty.

In any case, I can see why people call Ross the Cherokee Moses. Seems to me he was on the right side in most of the conflicts. He fought for Cherokee sovereignty and was willing to fight for the land. When removal was forced upon the Cherokees, he took over and made it work. He kept the tribe together through decades of dissension. When the Civil War loomed, he sympathized with the anti-slavery North.

All in all, I'd have to rank him right up there with great Indian leaders such as Tecumseh and Sitting Bull. A staunch chief for almost 40 years...tough to beat that.

Outsiders can't know Natives?

Incidentally, it's interesting that Ross was only 1/8 Cherokee by blood, while Ridge was something like 3/4 Cherokee. How is it that the mostly white leader took a more anti-US position than the mostly Native leader? People say it's impossible for non-Natives to understand Native thinking, but Ross seemed to manage it despite his Anglo blood.

If Native thinking is so unfathomable, how is it that Ross and Ridge disagreed about the correct course of action? Which one of them was channeling the Native mentality that outsiders can't understand? Who was the true Native in the situation: Ridge the appeaser or Ross the obstructionist?

Perhaps it as I've always said: that there are many different Native cultures and beliefs, some of them mutually exclusive. That no one person can speak for or represent all of Native America. That Natives are basically like the rest of us--some willing to die for their beliefs, others preferring to live and fight another day. The mystery is why some people try to obscure the basic humanity of everyone, including Natives.

For more on the subject, see Removal in Trail of Tears and Review of Trail of Tears.

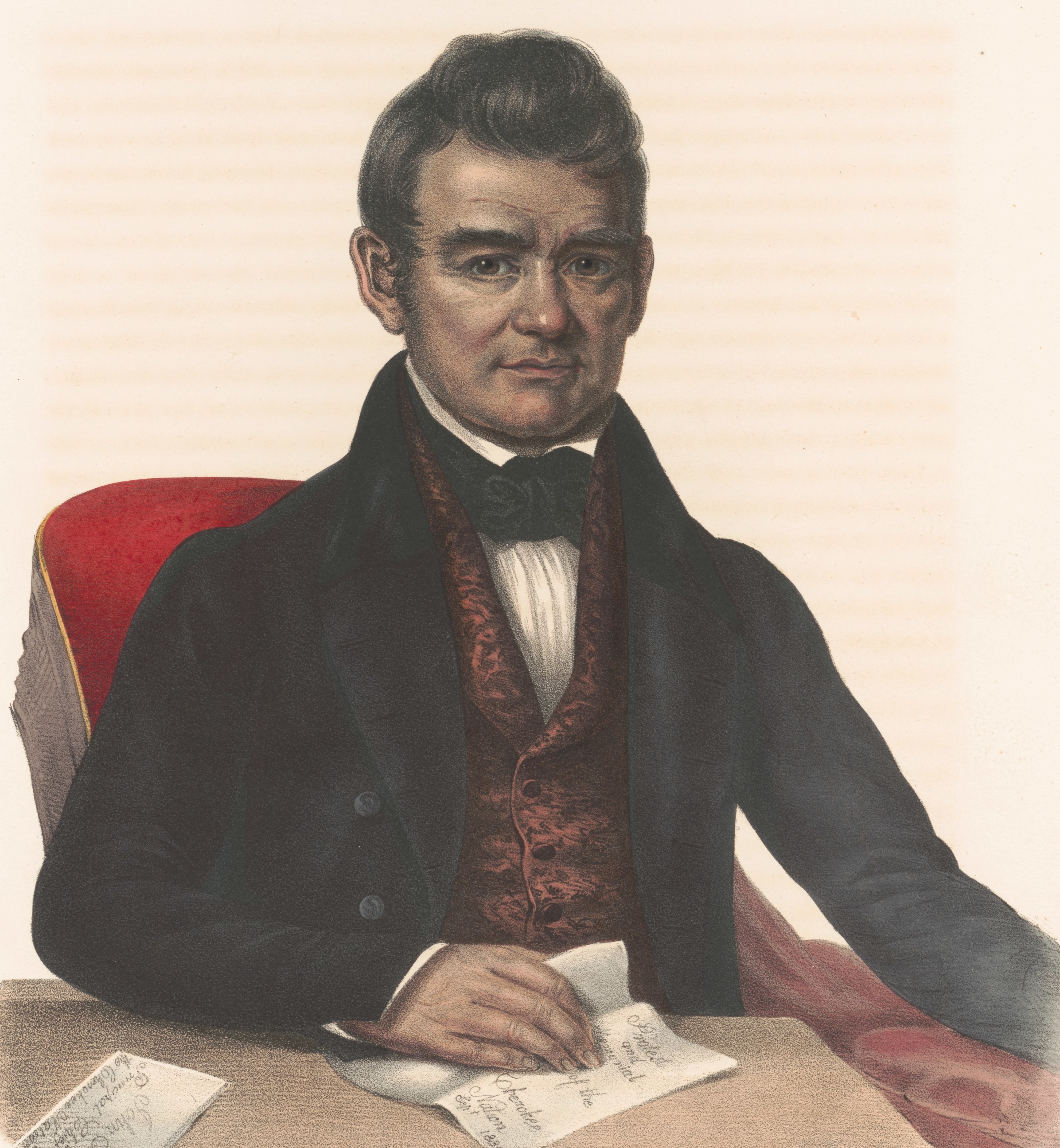

Below: Young John Ross.

4 comments:

"All in all, I'd have to rank him right up there with great Indian leaders such as Tecumseh and Sitting Bull. A staunch chief for almost 40 years...tough to beat that."

He was better than tecumseh since he didn't ally himself with a certain genocidial government.

"How is it that the mostly white leader took a more anti-US position than the mostly Native leader? People say it's impossible for non-Natives to understand Native thinking, but Ross seemed to manage it despite his Anglo blood."

I wouldn't exactly call him non-Indian, he was accepted by the Cherokees and became their chief, of course that's just my two non-Indian cents. Also calling Ross an anglo (ie English) is inaccurate since he was primarily Scottish (his name is of Norman origin). Intermarriage betweens Scots and Scots-Irish (although there's almost no difference between the two groups except for the fact that some ulster-scots had Irish blood) and Indians was actually very common for a number of reasons.

Also I'd wager Ross probably compared what was happened to Indians to this example of land theft and cultural genocide:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Highland_Clearances

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lowland_Clearances)

"People say it's impossible for non-Natives to understand Native thinking"

The more I think of it, the more this statement has a strong tinge of racism. It is also anti-intellectual. It pretty much is saying that ideas can't be evaluated objectively on their own merits, but must instead be evaluated based on the "race" of the person/thinker putting forth the idea.

Stephen, you have a great point when you say "I wouldn't exactly call him non-Indian, he was accepted by the Cherokees and became their chief"

It is not just your two non-Indian cents. This view is a central one to Rob's own points about what properly defines an Indian.

Thanks.

Post a Comment