(In explaining the importance of the feathers, actor Val Kilmer began his remarks with, "It might not sound like much...." Indeed.)

And...that's about it.

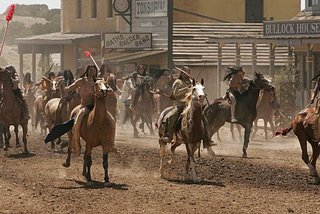

So the Indians in Comanche Moon looked and sounded like real Comanches. That's nice, but it's only the tip of the cultural iceberg. It isn't or shouldn't be a substitute for real culture.

I believe Buffalo Hump (Wes Studi) goes on a "vision quest" to hatch his revenge plot. I don't know for sure, but I'm guessing that's not the usual purpose of a vision quest. Other than that, Comanche Moon shows zero evidence of the Comanches' cultural beliefs and practices. It's as if Jonathan Joss's statement on Comanches is true: the people were nothing but murderous savages.

The reality

Here are a few postings that explain what Comanche Moon may have missed and why:

The Religion of the Comanche

The Nermenuh were also very secretive about their beliefs and believed that the efficacy of their "medicine" or powers derived from some natural force might well be eliminated or dimmed if discussed with or viewed by another. The Comanche did not have a coherent religion. They believed that many things in their surroundings had "powers" or "forces" that they might share in if they could just learn how to persuade the Sun, the Moon, the Buffalo or some other natural force to share a portion of their power. A totem or symbol of this power was then placed in their "Medicine pouch" around their neck and shared with nobody. But they did not believe that the sun was a god, nor the buffalo, nor the wolf. They were just creatures with power that they shared with certain human individuals when properly approached.

More Comanche culture

The summary above covers only the religious aspects of Comanche culture. Here are other aspects of Comanche culture that Comanche Moon omitted--presumably to make the Indians seem more savage.

Comanche

At one point, Sam Houston, president of the newly created Republic of Texas, almost succeeded in reaching a peace treaty with the Comanches, but his efforts were thwarted when the Texas legislature refused to create an official boundary between Texas and the Comancheria.

Comanche groups did not have a single acknowledged leader. Instead, a small number of generally recognized leaders acted as counsel and advisors to the group as a whole. These included the "peace chief," the members of the council, and the "war chief."

Sometimes a man named his child, but mostly the father asked a medicine man (or another man of distinction) to do so. He did this in hope of his child living a long and productive life. During the public naming ceremony, the medicine man lit his pipe and offered smoke to the heavens, earth, and each of the four directions.

The Comanche looked upon their children as their most precious gift. Children were rarely punished. Sometimes, though, an older sister or other relative was called upon to discipline a child, or the parents arranged for a boogey man to scare the child. Occasionally, old people donned sheets and frightened disobedient boys and girls. Children were also told about Big Cannibal Owl (Pia Mupitsi) who, they were told, lived in a cave on the south side of the Wichita Mountains and ate bad children at night.

When he was ready to become a warrior, at about age fifteen or sixteen, a young man first "made his medicine" by going on a vision quest (a rite of passage). Following this quest, his father gave the young man a good horse to ride into battle and another mount for the trail. If he had proved himself as a warrior, a Give Away Dance might be held in his honor.

Boys might boldly risk their lives as hunters and warriors, but, when it came to girls, boys were very bashful. A boy might visit a person gifted in love medicine, who was believed to be able to charm the young woman into accepting him.

Old men who no longer went on the war path had a special tipi called the Smoke Lodge, where they gathered each day. A man typically joined when he became more interested in the past than the future.

Like other Plains Indians, the Comanche were very hospitable people. They prepared meals whenever a visitor arrived in camp, which led to the belief that the Comanches ate at all hours of the day or night. Before calling a public event, the chief took a morsel of food, held it to the sky, and then buried it as a peace offering to the Great Spirit. Many families offered thanks as they sat down to eat their meals in their tipis.

You won't learn any of this from Comanche Moon. What you will learn is largely negative. As I wrote in Comanche Moon: Rangers, Tramps, and Thieves: