By Jason Easley

Every time his conservative foes see President Obama, they are reminded that our nation is changing. When the see the black man occupying the White House they are confronted by their loss of power. The White Republicans feel entitled to the presidency. It is their unfailing belief in their own superiority that is the basis behind their obsession with criticizing Obama as incompetent at every turn. If they can only make America belief that the black president is incompetent then they can be restored to their god given position of lord and master over us all.

It’s not Obama’s dark skin, but what his dark skin represents that evokes hatred without bounds and limits. President Obama’s power of them and the realization that their status as a privileged class is coming to an end are the real reasons why they disrespect President Obama.

Hatred is the fuel of fear, and for white conservatives their hatred of Obama masks the fear attached to the realization that their America is never coming back.

By Mark Karlin

TW: I think it did. It's not that the election of Obama caused the racism of course, but it certainly gave those with deep seated racial resentments and anxieties a new opportunity to articulate those under the guise of mainstream politics. The election of a man of color challenges the fundamental notions that many whites have long had, about what a leader is supposed to look like. And since this particular president is not only a man of color, but also has a name that seems "exotic" to some, and had a father who wasn't even African American, but rather, straight off the continent of Africa itself, the sense of otherness surrounding him is even greater. He stands as something of a symbol of the transition from the old, white narrative of America to a new, multicultural, multiracial norm - and it's a norm for which many, many whites simply are not prepared and about which they are not pleased.

MK: Why is it that so many poor whites--let's say in Appalachia--feel closer to white billionaires, who care nothing about their economic plight, than poor minorities, who share their economic travails?

TW: First, because they have been subjected to intense racial propaganda for generations, which has sadly left them clinging to what DuBois called the "psychological wage of whiteness," which means the psychological advantage of believing oneself superior to someone, anyone of color, even though you are suffering economically. Unfortunately, when your real wages and working conditions are poor, the weight of the psychological wage intensifies and can become a crutch to which one clings in moments of insecurity. Also, the U.S., more so than elsewhere, has cultivated the notion that "anyone can make it" if they try hard enough. Unlike the feudal monarchies of Europe, where the poor and working class knew full well they were never going to be on top, here, the reigning ideology--the secular gospel if you will of America--is that individual initiative trumps all. If one believes that, then it becomes less likely that one will problematize the rich, or criticize them, or seek to challenge them, because at some level, even the poorest persons hope that one day they will be one of them--or if not rich, at least comfortable. So class consciousness becomes harder in such a place, and yet, when one's class position doesn't rise very much from generation to generation (and for many whites it still doesn't), they content themselves with their perceived superiority relative to persons of color, and settle for that, rather than fighting for a better deal for all workers, white and of color.

Is the Era of White Privilege Nearing an End in the US?

By Tim Wise

In other words, the past is the past, and we shouldn’t dwell on it. Unless of course we should and indeed insist on doing so, as with the above-referenced Independence Day spectacle, or as many used to do with their cries of “Remember the Alamo” or “Remember Pearl Harbor.” Both of those refrains, after all, took as their jumping-off point the rather obvious notion that the past does matter and should be remembered - a logic that apparently vanishes like early morning fog on a hot day when applied to the historical moments we’d rather forget. Not because they are any less historic, it should be noted, but merely because they are considerably less convenient.

Oh, and not to put too fine a point on it, but when millions of us have apparently chosen to affiliate ourselves with a political movement known as the Tea Party, which group’s public rallies prominently feature some among us clothed in Revolutionary War costumes, wearing powdered wigs and carrying muskets, we are really in no position to lecture anyone about the importance of living in the present and getting past the past. All the less so when the rallying cry of that bunch appears to be that they seek to “take their country back.” Back, after all, is a directional reference that points by definition to the past, so we ought to understand when some insist we should examine that past in its entirety, and not just the parts that many of us would rather remember.

Truth is, we love living in the past when it venerates this nation and makes us feel good. If the past allows us to reside in an idealized, mythical place, from which we can look down upon the rest of humanity as besotted inferiors who are no doubt jealous of our national greatness and our freedoms (that, of course, is why they hate us and why some attack us), then the past is the perfect companion: an old friend or lover, or at least a well-worn and reassuring shoe.

If, on the other hand, some among us insist that the past is more than that--if we point out that the past is also one of brutality, and that this brutality, especially as regards race, has mightily skewed the distribution of wealth and opportunity even to this day--then the past becomes a trifle, a pimple on the ass of now, an unwelcome reminder that although the emperor may wear clothes, the clothes he wears betray a shape he had rather hoped to conceal. No, no: the past, in those cases, is to be forgotten.

Vast numbers of us, it appears, would prefer to hermetically seal the past away in some memory vault, only peering inside on those occasions when it suits us and supports the cause of uncritical nationalism to which so many of us find ourselves imperviously wedded. But to treat the past this way is to engage in a fundamentally dishonest enterprise, one that, in the long run (as we’ll see), is dangerous. Unless we grapple with the past in its fullness--and come to appreciate the impact of that past on our present moment--we will find it increasingly difficult to move into the future a productive, confident and even remotely democratic republic.

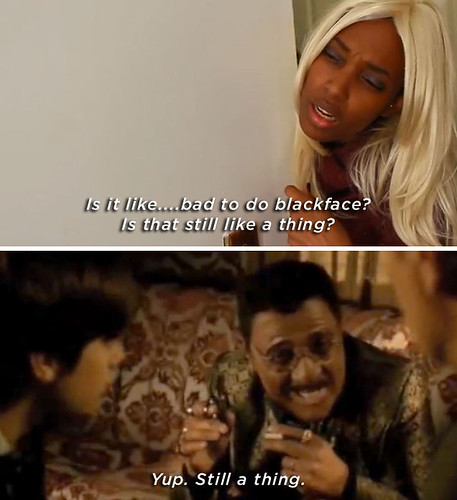

For more on white privilege, see Racist Costumes = White Privilege and Whites "Sick of the Race Card."