By Hillary Rodham Clinton and Jonas Gahr Store

Ten years ago this week, the United Nations took a historic step in this direction by recognizing that women are not merely victims of war, they are also indispensable agents of peace. Yet progress in including women in the peacemaking process has lagged. On this anniversary of the unanimous passage of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that women are at last seated at the negotiating table--and in meaningful roles.

It is indisputable that women and children suffer disproportionately from war, including as targets of rape. We must do more to protect them. But relegating them to the role of passive victims keeps them powerless. When the “victims” organize, they are potent advocates for change, as they were in Sierra Leone, Rwanda and Liberia.

Women can be effective peacemakers because they have a broad view of security. To them, it is more than the absence of armed fighters. It means their sons and daughters can go to school safely. It means they can get medical attention when they give birth, and have their children vaccinated. It means returning refugees can find land, water and jobs. Broadening our definition of security in this way helps prevent simmering grievances from recurring and escalating.

Of course, including women does not guarantee that peace talks will succeed. But recent history shows that agreements that exclude women and ignore their concerns usually fail.

I often criticize America as a macho, violent, cowboy, warrior country. I've said our national anthem should be Be a Victor or Be a Victim. I've said our literary heroes are modeled on Hercules. And so forth.

We're quick to engage in fistfights, shootouts, and wars because that lets us prove our manhood. We build ourselves up as the toughest guy on the block, able to lick anyone in the house. Our national self-image is rugged individualism.

If people like the French aren't as eager to fight, we call them sissies and wimps at best, cowards and traitors at worst. We question their manhood. We suggest they're gay--perhaps the ultimate insult to a red-blooded American.

We build up our enemies to be even more macho than we are. We call them savages, barbarians, or Huns. That way, we can congratulate ourselves when we defeat them. "They thought they were tough but we proved we were tougher."

What about Indians?

When we look back at foes such as Indians, we're of two minds. If it's in a warlike setting--e.g., the military or sports--we emphasize their warrior qualities. We still want to reward ourselves for beating them.

It's like wearing a bearskin cloak or necklace made of claws. An Indian name or image is like a trophy from a successful hunt. We came, we saw, we conquered, and here's the proof.

But if it's not a warlike setting, we emphasize their "inferior" cultural and spiritual qualities. We say they're lazy, ignorant wastrels who can't hold a job and drink too much. We think they can't learn or change, can't cope with the modern world. We say they're like children: immature, mercurial, and ungovernable. Or like spirits: strange, dark, and mysterious.

All this is similar to what we've said about women through the ages. For instance:

Female hysteria

The history of hysteria can be traced to ancient times; in ancient Greece it was described in the gynecological treatises of the Hippocratic corpus, which date from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. Plato's dialogue Timaeus tells of the uterus wandering throughout a woman’s body, strangling the victim as it reaches the chest and causing disease. This theory is the source of the name, which stems from the Greek word for uterus, hystera (ὑστέρα).

Shared values

But the Indians who were warlike gave up their "wild" ways when they settled on reservations. What's left are the core values that I talk about frequently: caring for the community, stewarding the environment, thinking seven generations ahead. Indians don't boast and dominate a room; they stay quiet and listen. They don't impose their religions on others; they let everyone worship in their own way. They don't send people to jail; they resolve conflicts through talking circles.

All these are generalizations, of course, but I think they're generally true. There's a large overlap between female values and indigenous values. Men want quick, tough, focused solutions. If someone hits you, fight back. Women and Natives take the long view, make webs of connections, and focus on healing and nurturing. If someone hits you, talk to him and learn what's wrong. Find a permanent solution, not a temporary Band-Aid.

Americans obviously favor the male way of thinking. They'd rather fight than switch. Our purpose here is to suggest an alternative perspective. Both women and Natives provide that. They offer a different way of looking at the world.

Hence the Clinton/Store thesis that women are or should be peacemakers. If the world adopted more of the female or Native perspective, it would be a better place.

For more on this clash of values, see:

Columbus the cannibal

National Day of the American Cowboy

Arizona laws = manifest insanity

Conservative worldview = fear of cooties

Why Americans keep killing

For more the female/Native nexus of values, see:

Indians inspired feminism

A Latin view of American-style violence

Diplomacy works, violence doesn't

Winning Through nonviolence

Hercules vs. Coyote: Native and Euro-American beliefs

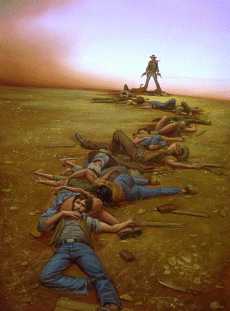

Below: The Western/male way of dealing with conflicts and...

...the Native/female way.